|

| The "Monty Hall Problem" |

This post is about yet another reason to distrust "circumstantial evidence" in a court room situation.

There is a tendency in the human mind to impress upon situations what we "think" is probable. As an example imagine that I ask a large audience to sit facing me. I flip a coin five times and, while not letting the audience see the result, I claim to broadcast the results psychically to the audience. I ask them to write down the heads/tails sequence they believe I am sending them.

I next explain that its very unlikely anyone will have received my psychic transmissions correctly because, well, that would require psychic transmissions to be real. So I reveal the actual coin sequence, for example, THHTH (T = Tails, H = Heads) and, surprisingly, a number of people raise their hands and show that they have in fact written down the correct sequence of heads and tails.

(This example is summarized from this.)

At issue here is the audiences expectation of randomness (and presuming also that no actual psychic transmissions are occurring). Any non-mathematician audience member is likely to write down something that to them does not appear to be random, i.e., they will likely not write down HHHHH, TTTTT or THHHH, even though these outcomes for five coin flips are just as likely as any others. Instead they are likely to write down something like HTHHT which to their mind's experience appears to be more "random" and hence more likely.

Should I actually flip HHHHH or TTTTT then probably no one will get it right. But more often than not I will flip something that appears to match our expectations of "randomness" and someone will have made up a random sequence to match.

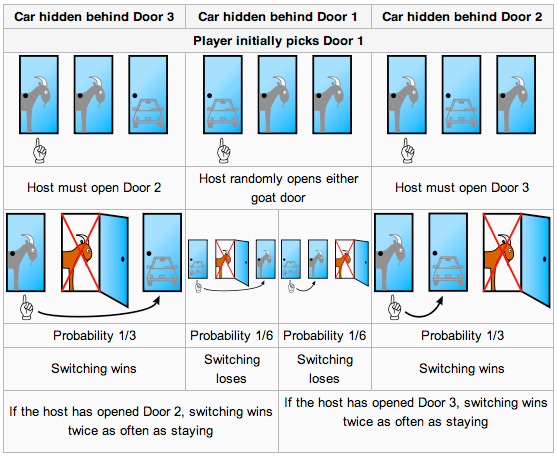

Another example of this type of confusions is called "The Monty Hall Problem" (see this video for a clear explanation). This is another example of a counter-intuitive result based on what looks like a simple probability problem.

Given these types of examples I am going to now claim that by using circumstantial evidence is a court room situation there is much more than the prosecutor trying to claim that A implies B implies C where there is no direct evidence in the chain of events.

So imagine that the prosecutor, knowingly or not, assumes the roll of me in the first example above. The jurors are the "audience members". Now by presenting the facts in such a way as to control the outcome the jury expects to see the prosecutor has a distinct advantage over the defense.

The first advantage is the mere fact that the court case has gone to trial at all. The jury must, even subliminally, believe that there is at least some merit to the charges otherwise there would not be a trial at all. In my example this is the role of "psychic transmission" (some 70-80 percent of the population believes in the paranormal according to this).

Next the prosecutor divulges a "theory of the crime". This involves demonstrating a logical chain of deduction going from the crime backward (or forward) through some chain of reasoning to the defendant. Something like:

E: "Joe killed Sally."

D: "Sally is dead of a gunshot wound."

C: "Joe was at Sally's house the day she died."

B: "The day before Sally is found dead Joe bought a gun."

A: "The week before Sally told Joe their relationship was over."

So the prosecutor tells the jury that A implies B implies C implies D implies E. The desire is that the jury converts each of the "implies" steps along the way to "causes", essentially like writing down the expected result of the coin toss.

In cases with all or mostly circumstantial evidence, as with Casey Anthony, this is the only real chance for the prosecution: to convince enough of the jurors that they guessed at or concluded the same implications between each of the steps as the prosecutions theory put forth.

To convict someone of a crime you actually need a causal link between the events, e.g. A caused B, that leaves no room for doubt. Yet, like the coin toss example, if you have a propensity to believe something (paranormal or that no mother would kill her own child) to begin with your mind is going to fabricate the "causal" implications for you.

The problem, of course, is that there isn't necessarily any link at all between each of the events, just as there is no link between the results of one coin toss and the next.

So, based on circumstances and without causal links between events your predisposition to believe something is going to be what drives your conclusions.

Yet people, due to reasons they may not even know, create these implications out of whole cloth. They literally make up links between events just like they make up "random" coin toss results.

Most people, and even many mathematicians, have a hard time excepting the "Monty Hall Problem" because it is so counter-intuitive. And given a jury of lay people, more than likely without even basic mathematical training in probability, its a good bet no one will see beyond the theory of the prosecution to the weak logical foundation upon which it must rest (if there was real evidence people would expect to have seen it - again just like the Casey Anthony trail).

When there is a discussion of the apparently non-existent "CSI Effect" among prosecutors it is much more likely they are seeing the results of education over the centuries. In the 1600's people believed in witchcraft as an actual "cause" for things and few had any education at all. Today most people have at least heard that paranormal events are not real and have probably had to sit through at least one year of mathematics education where probability is presented.

Its little wonder today's juror is going to expect more than the A, B, C, D, E I presented above as the reason to convict Joe.

And this is not what the shrieking female talking head prosecutors want to hear - because causally linking A to B and so on is hard. Much harder than they are perhaps used to.

No comments:

Post a Comment